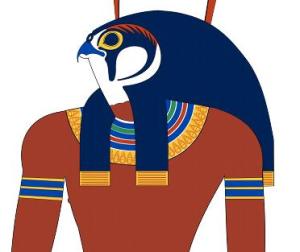

One of the most evocative symbols in hieroglyphics is the Eye of Horace, god of the pharaohs, often depicted as a human with a falcon head, which is a nice head to have if you’re an ancient deity. Far more preferable than dog-headed Anubis, or crocodile-faced Sobek.

Horace was the fortunate son of Osiris and Isis until his bastard uncle, Set, god of the desert, storms and chaos, murdered his brother, Osiris, leaving divine sovereignty up for grabs. Horus had no choice but to engage his uncle in an all out brawl for power. Let the game of thrones begin.

Set, whose head is an unfortunate cross between a jackass and an aardvark, loses a testicle in the fight, which is why the desert is infertile. Horus loses his left eye, but he ends up winning the day and the throne, making him King of all the living. His eye is magically regenerated, and the image takes its place in the Egyptian pantheon as a symbol of protection, sacrifice, healing and regeneration.

Set, whose head is an unfortunate cross between a jackass and an aardvark, loses a testicle in the fight, which is why the desert is infertile. Horus loses his left eye, but he ends up winning the day and the throne, making him King of all the living. His eye is magically regenerated, and the image takes its place in the Egyptian pantheon as a symbol of protection, sacrifice, healing and regeneration.

All timely virtues, especially in lieu of recent terrorist events in Algeria.

Algeria is Morocco’s more turbulent, less tractable neighbor, and the country is still reeling after the beheading of French tourist Herve Gourdel. “Heinous, cowardly, criminal, despicable,” are the words being bandied about after the latest ISIS offensive. Our production’s stalwart security detail has assured us that our scenario 600 miles away in Ourzazate is far safer. But beneath the calm reassurances, one senses an escalation from DEFCON 5 to 4.

The unfortunate, and thoroughly un-ironic coincidence, is that our props department has used the very same words– cowardly, criminal, despicable– to describe Moroccan customs, who have refused to release the silicon decapitated heads we spent thousands of pounds creating in London for the show. We’ve already shot a scene without them that we’ll have to CGI in post. This is how productions go over budget.

The unfortunate, and thoroughly un-ironic coincidence, is that our props department has used the very same words– cowardly, criminal, despicable– to describe Moroccan customs, who have refused to release the silicon decapitated heads we spent thousands of pounds creating in London for the show. We’ve already shot a scene without them that we’ll have to CGI in post. This is how productions go over budget.

It seems utterly irrelevant considering the reality of events in Algeria, and perfectly understandable given the graveness of the act, and yet, the show must go on. One of the better ways to battle such extremist irrationality is through art.

Our fake heads aren’t the only things being withheld by customs either. Nor are we the only production here being extorted to get our property back. It’s a common maneuver in these parts– almost as common as the long tradition of beheading– and a reliable revenue stream for the officials in charge. This is a land where competition for resources has always been cutthroat. Get whatever you can, whenever you can. Intimidate the enemy. Show ’em you mean business. Take their heads off if you have to.

For thousands of years, Northern Africa was a region of warring tribes. The Berbers and Bedouin dominated, often battling each other for access to natural resources. When one tribe damned a river upstream, the other attacked to smash it down. The tribes were fiercely independent and proudly self-reliant… until the infidels arrived. That’s when everything started changing. That’s when the real threat to lifestyle and culture happened.

The soil in Morocco has always been mineral rich, and it wasn’t long before French, Spanish, Italian and German colonials were competing to cultivate it, always with an eye towards enhancing markets back home. These visitors were not here to share. They wanted to take it all for themselves, as foreigners will. Forgetting, all too easily, that the context from which these things are ripped is precicely what gives them their value.

The French achieved a commanding foothold prior to the first World War, exploiting the land for fruit, vegetables and vineyards. Thousands emigrated, pressuring Paris to tighten its grip in order to protect their newly planted interests. As the capital complied, the Berbers fled into the mountains, refusing the occupation. But other tribes embraced the French new wave, happy to fill the power vacuum. In return for their cooperation, the French modernized the agricultural and transportation sectors– upgrades Morocco still benefits from today.

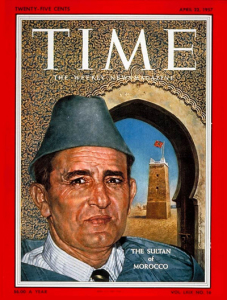

The tipping point came when the French unwisely exiled Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar in 1953 and replaced him with their puppet, Mohammed Ben Aarafa. The maneuver had the opposite of the intended effect, uniting the warring tribes who suddenly saw their religion threatened. Protests occurred. Violence rose. Expats panicked their investments were exposed. The Sultan’s return was demanded and the French had no choice but to reinstate Mohammed V. But the tides had already turned, and shortly thereafter in 1956, Morocco won its independence. They’ve been autonomous ever since, and have miraculously ingratiated the French influence with little resentment.

The tipping point came when the French unwisely exiled Sultan Mohammed V to Madagascar in 1953 and replaced him with their puppet, Mohammed Ben Aarafa. The maneuver had the opposite of the intended effect, uniting the warring tribes who suddenly saw their religion threatened. Protests occurred. Violence rose. Expats panicked their investments were exposed. The Sultan’s return was demanded and the French had no choice but to reinstate Mohammed V. But the tides had already turned, and shortly thereafter in 1956, Morocco won its independence. They’ve been autonomous ever since, and have miraculously ingratiated the French influence with little resentment.

No film production could succeed in Ourzazate without the predominantly French speaking workforce that calls this city of 200k home. For Spike TV’s maiden series Tut, some five hundred craftsmen and women arrive daily at the gates of Atlas Studios to hammer nails, plaster statues, weave palms, sew fabric, paint sets and smith metal, all without the use of power tools. There isn’t a nail gun in the entire city. The work day is roughly twelve hours long. Compensation is 150 Dirham, about $18.

No film production could succeed in Ourzazate without the predominantly French speaking workforce that calls this city of 200k home. For Spike TV’s maiden series Tut, some five hundred craftsmen and women arrive daily at the gates of Atlas Studios to hammer nails, plaster statues, weave palms, sew fabric, paint sets and smith metal, all without the use of power tools. There isn’t a nail gun in the entire city. The work day is roughly twelve hours long. Compensation is 150 Dirham, about $18.

Compensation notwithstanding, the plaster and paint departments work some serious movie magic creating these ancient Egyptian sets. You’d never in three thousand years know that the majority of these locations are merely a mix of lime, sand and water, because when our hi-def Alexa cameras pan across them, they look more real thing than the real thing. This is post-post-modern antiquity at its very best. Baudrillard would be proud.

Compensation notwithstanding, the plaster and paint departments work some serious movie magic creating these ancient Egyptian sets. You’d never in three thousand years know that the majority of these locations are merely a mix of lime, sand and water, because when our hi-def Alexa cameras pan across them, they look more real thing than the real thing. This is post-post-modern antiquity at its very best. Baudrillard would be proud.

And that’s not to take away from our killer locations. We shoot this week in the iconic, pre-Saharan habitat of Ait-Ben-Haddou. The earthen abodes crowded together along the southern slope of the Atlas mountains were a trading post on the commercial route linking ancient Sudan to Marrakech by the Tizi-n’Telouet Pass. Say that six times quickly.

This particular village, known as a Ksar, was built in the 17th Century, but the architectural technique is hundreds of years older. It differs from the fortress-like Kasbah, which is always comprised of four towers and an open center. A Ksar is more a collection of family dwellings, with a mosque, a public square, and grain threshing areas, for the threshing of grains, of course.

But the inhabitants of Ait-Ben-Haddou weren’t without their concerns for protection. The entire settlement exists behind large defensive walls, which are reinforced by angle towers and zigzagging gates. Their daily prayers for safety and healing were to Allah by this time, but you can be sure Horace wasn’t far off, hovering above, shedding grace from his aerie, his protective eye preserving the sacred Maghreb, just as he does now… for us. In return, we’ll further immortalize his extraordinary story, and for a global television viewership, no less.

We’re going to need your help when this thing airs next July. If ratings aren’t high, we could easily incur the deity’s wrath…

Permalink

Great stuff Al. Keep these coming. Loving the Moroccan history lesson. Surprisingly, I was already familiar with Horus and Set and Osiris and Isis from reading a couple of those Rick Riordan (The Kane Chronicles) books with Holden. Can’t wait to read your this latest missive with Holden this weekend. He’ll totally dig it. Be safe and keep the show rolling.

Permalink

Dear Alex,

Thank you for your wonderful missives.

I think a movie about the making of this movie and the background would be wonderfully compelling.

What an experience you are having. Thank you so much for keeping us informed and as they say, ‘sharing’.

Much love,

Joan

Permalink

I love these missives.

Permalink

i hope you have time to take a cooking class Alex! ❤️Be safe & we look forward to more stories straight from your mouth!

Permalink

I’m a long time fan of great movie / TV productions and I really appreciate the details and narrative with this behind the scenes blog of TUT, currently filming in Morocco. I knew it was a major production, but as a person who has never visited a set, I just couldn’t begin to imagine the level of detail that goes into the planning and production, right down to the hand thrown clay cups. Your descriptions and pictures provide a view that I’ll never have a chance to see. And the number of people involved seems staggering. Huge fan here, and I hope you’ll continue! I’m enjoying every bit!