Making television is a high pressure gig. If you’re in a crucial position, one mistake will have you packing your bags– fired and replaced– before the footage gets downloaded from the camera.

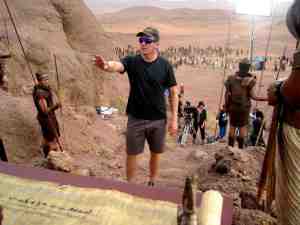

The Director stands in the eye of the storm, helming the multitudinous cast and crew through non-stop Scylla and Charybdis. All of the pressure that comes with spending hundreds of thousands of dollars daily rests on his shoulders. A sharp director surrounds himself with men and women he can rely in the crunch, or sacrifice to the executive gods when push comes to shove. His most crucial ally is the cinematographer, (aka director of photography.)

The cinematographer and the director collaborate on composing every single image you see in the final product. A great D.P. is a master visual artist, painting with shadows and light. He can tell you the time of day with frightening accuracy just by glancing up at the sun as he juggles a dizzying array of elements to breathe life into the words on the page: lenses, filters, aspect ratios, depth of field, framing, focus pulling, and camera movement are all carefully considered. The D.P. relies on another team of experts to manifest his vision when action! is yelled.

The cinematographer and the director collaborate on composing every single image you see in the final product. A great D.P. is a master visual artist, painting with shadows and light. He can tell you the time of day with frightening accuracy just by glancing up at the sun as he juggles a dizzying array of elements to breathe life into the words on the page: lenses, filters, aspect ratios, depth of field, framing, focus pulling, and camera movement are all carefully considered. The D.P. relies on another team of experts to manifest his vision when action! is yelled.

The 1st Assistant Director (A.D.) manages a mind blowing array of logistics– from arranging a three month production schedule, to pulling that schedule off once the shoot begins, hour by hour, minute by minute. Fall behind schedule and things start falling apart. He’s constantly catering to the cast and crew, all of whom have specific needs and demands, some of which can test the most composed professional’s patience. He must also maintain order on set, an especially onerous task when half of your people are speaking a rapid-fire mishmash of Arabic-French-Berbere, fueled by an explosive cocktail of caffeine, carbs and cigarettes, and the cultural inclination to argue at full volume as a sign of affection. The AD is the guy on set with the walkie-talkie attached to his face, keeping it all together and on track, RIGHT NOW.

The 1st Assistant Director (A.D.) manages a mind blowing array of logistics– from arranging a three month production schedule, to pulling that schedule off once the shoot begins, hour by hour, minute by minute. Fall behind schedule and things start falling apart. He’s constantly catering to the cast and crew, all of whom have specific needs and demands, some of which can test the most composed professional’s patience. He must also maintain order on set, an especially onerous task when half of your people are speaking a rapid-fire mishmash of Arabic-French-Berbere, fueled by an explosive cocktail of caffeine, carbs and cigarettes, and the cultural inclination to argue at full volume as a sign of affection. The AD is the guy on set with the walkie-talkie attached to his face, keeping it all together and on track, RIGHT NOW.

The Gaffer, as you know from watching the movie credits roll, deals with all of the set’s high-voltage electricity needs. It’s a dangerous gig, especially when your studio has a comically leaky roof in a hard seasonal downpour. That’s when he reminds to Best Boy, his 1st assistant, to dry his hands before plugging anything in. Daylight Savings Time just robbed us of an hour of light a day, so artificial illumination has become more important than ever.

High powered fixtures can turn night into day with relative ease, and the massive cables that snake from those lights to the truck-sized generators are only ever handled by the Gaffer’s team of Electricians.

High powered fixtures can turn night into day with relative ease, and the massive cables that snake from those lights to the truck-sized generators are only ever handled by the Gaffer’s team of Electricians.

Grips, as you assumed, grip things. Specifically, things that are not electrically charged: c-stands for holding those massive lights, sandbags for keeping those c-stands from tipping over, rubber walkways to cover the cables so the actors don’t trip and knock their teeth out, flags for blocking light, reflectors for bouncing light, gobos for casting shadow patterns– there are more tools than you can possibly imagine shape the scene being painted for the camera.

They are all essential positions, but one of the true unsung heroes behind-the-scenes is the Script Supervisor. The importance of a good one can’t be overstated.

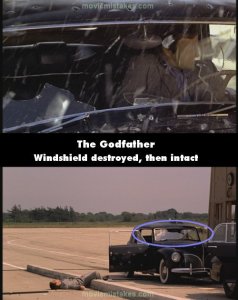

The position is comprised of innumerable responsibilities, but maintaining continuity is the most imperative. Actors must deliver their lines and reenact their behavior consistently, from take to take– wide, medium, close up– so it all cuts together in the editing room. In essence, the script supervisor is a real-time, on-set editor.

Pending errors lurk like booby traps in every scene. Actors mix up word order, their hair falls on different sides of their faces, props get moved from take to take to take. The Script Supervisor interacts with every department– writing, sound, camera, props, lighting, hair and make-up, costume– catching the never ending bevy of minute inconsistencies.

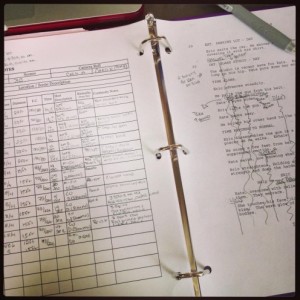

There are also issues with how scenes are shot. If the director ends one scene on a close up, he probably doesn’t want to start the next scene in the story (which may be shot weeks later) with another close up. A Script Supervisor has logged all this information– what lense was used, the angle it started and ended on, and what the director felt was the best take at the time– and will now suggest establishing the next scene with a wide angle before moving in tighter.

There are also issues with how scenes are shot. If the director ends one scene on a close up, he probably doesn’t want to start the next scene in the story (which may be shot weeks later) with another close up. A Script Supervisor has logged all this information– what lense was used, the angle it started and ended on, and what the director felt was the best take at the time– and will now suggest establishing the next scene with a wide angle before moving in tighter.

These are issues you might never catch on a first viewing, but you’d have an unconscious sense that something was off, and it would take you out of the scene. Watch a film five or six times, and you start to notices the mistakes.

IMDB.com dedicates sections of their website to pointing out continuity errors. There’s a list of the top 250 most famous mistakes. Where a small continuity error might be cause for embarrassment, a big one can force the production to throw away an entire scene, forcing you to deal with the dreaded “R” word: Reshoot— a logistical, and pricey nightmare.

And while physical continuity is important, it’s not nearly is vital as emotional continuity. Film and tv shows are never shot in story order. Two scenes that are back to back when you’re watching in your living room were likely shot days, weeks, even months apart.

Location is king when you’re organizing a shoot. For efficiency, you need to schedule and shoot everything in that location before leaving for a new one, regardless of when it happens in the story. Moving all those trucks and lights and actors and catering tables is expensive and time consuming, so it’s not uncommon for an actor to do a scene, change costume, and do another scene from a different part of the timeline in the story in the same day, in an effort to “shoot out” that specific location and move on.

Keeping it all consistent falls to the Script Supervisor– taking meticulous notes in a giant binder for every shot, reminding the director that in the last scene, King Tut was wounded and limping with his left leg, or that the Queen is having a torrid affair and is slightly paranoid her servant won’t keep the secret. The director needs to be reminded of these emotional arcs because those preceding scenes in the story were shot five weeks ago, and he’s had three thousand other things to deal with since.

For the record, if you ever find yourself in a relationship with a Script Supervisor, don’t even think about trying to bullshit them. You’ll say, “I told you I was going to be late ‘cause I had a meeting!” And she’ll say, “No, what you said was, You might have a meeting and would let me know when you found out. You coughed twice, nervously, opened the door with your right hand, and left the house with the top two buttons of your shirt open and your belt buckle notched to the third hole. Now your shirt has three buttons open, and your belt is notched to the fifth. Who are you having an affair with, you bastard?!”

In the movie version of this scenario, she grabs an iron skillet and hurls it at the philandering boyfriend, hitting him square in the left foot. He drops to floor, reaching for the injured limb in agony. She’s still keeping track of it all, as she has trained herself to do through years of scrupulous observation, and reminds the son of a bitch to limp with the proper foot in the following scene.

In the movie version of this scenario, she grabs an iron skillet and hurls it at the philandering boyfriend, hitting him square in the left foot. He drops to floor, reaching for the injured limb in agony. She’s still keeping track of it all, as she has trained herself to do through years of scrupulous observation, and reminds the son of a bitch to limp with the proper foot in the following scene.

Permalink

Wonderful post! Sorry there is only one more to come. Enjoy the rest of your shoot, Alex.

Permalink

Everything I learned in 2 years of film school summed up right here.

Permalink

Love this!

Permalink

I really look forward to these Morocco missives. Sign on to another movie over there if you have to, even if its about Zombies, but send us more of this entertaining reports.

Permalink

After 81 @#$% years, some one took the time to finally ‘splain all this to me.

This was very enlightening, bet I wasn’t the only ignoramus.

Permalink

I wish you were staying another few months so you would keep writing these!

Permalink

How any movie gets made is a minor miracle. Especially in an African dessert! Congrats on the show.