Santa Monica Daily Press

Searching for the Disappeared Mind

By Cynthia Citron

Feb. 2, 2017

Where does the mind go when its body is in a coma?

Playwrights Alex Lyras and Robert McCaskill explore this question in their provocative new play, “Plasticity,” now having its world premiere at the Hudson Guild Theatre in Los Angeles.

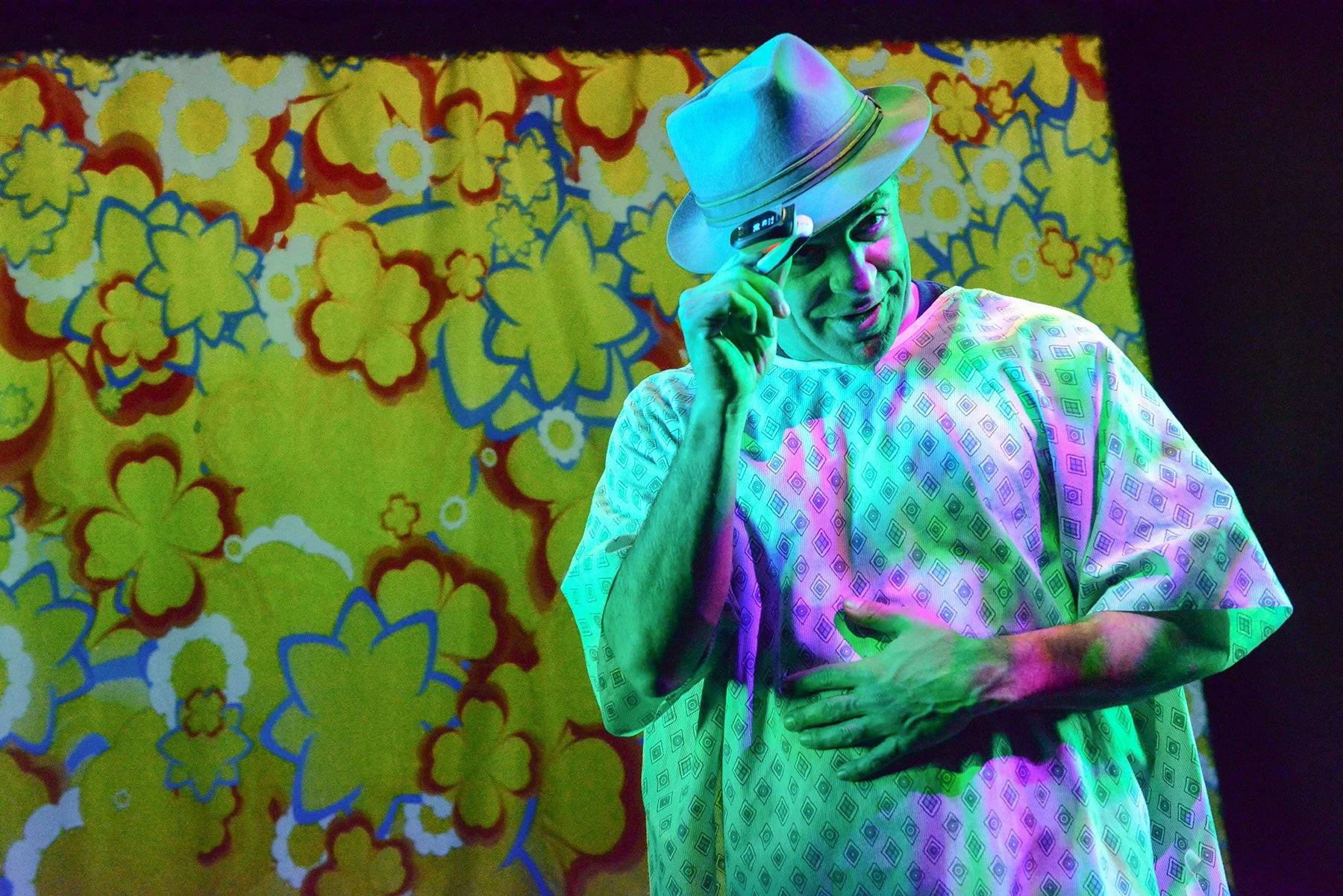

With multiple projections on a screen in the background and more projections on a see-through scrim in front, Lyras, sandwiched between the two screens, transforms himself, with a change of jackets, a pair of glasses, and a range of voices, into a myriad of doctors, hospital attendants, and concerned loved ones who hover around the bedside or on the phone to follow the treatment of a comatose patient, David Rosely.

David, an inveterate risk-taker, has fallen off a rocky mountain in the midst of a climb and now lies immobile in a hospital bed. The agonizing decisions about when to “pull the plug” fall to his identical twin brother, Grant.

Meanwhile, we are pulled into the confused mind of David as he struggles to retrieve his consciousness. This struggle is reflected in the bright colors and Rorschach squiggles that flash across the rear screen. They are accompanied by brief snatches of memory and ephemeral ghost-like abstractions spinning kaleidoscope-style.

“Who is the man?” asks one of the doctors. “He is the soul in the skin,“ answers another. “The brain is the antenna that picks up the soul,” says a third. “His brain will find a way to live.”

“But only on a par with a fetus in the womb,” says Mr. Bones, an orderly who appears from time to time to offer an update on everyone’s current concerns and emotions, which he disseminates in exquisite rhyme.

In addition to the activities at the hospital there are several very human subplots going on as well. Grant speaks regularly on the phone to his wife, Meg, to keep her apprised of David’s unchanging condition and to confess his own trepidation at having to make life-and-death decisions for a brother he dearly loves.

Then there is Kate, “six feet tall, and stunning” who claims to be David’s fiancee. Her loyalties waver between dedicating her life to taking care of David (“It will give my life a purpose,” she says) and hiring an attorney to forge documents that will identify her as the intended beneficiary of David’s estate.

As the weeks go by, David is force-fed through a tube and then, alternatively, not fed at all so that undernourished, he can wither away and die. “Doctors don’t believe in miracles,” says one. “Life is creative fiction,” says another. But then, after nearly two months, David hesitantly opens one eye. And the audience is guided through the processes and images that ultimately lead David to recover his mind.

Lyras, the solo actor who portrays all the characters, and McCaskill, who directs the play as well as co-writing it, did extensive research into brain plasticity, a term that refers to the ability of the brain to modify its own structure and function even after changes take place within the body or in the external environment.

“The latest neuroscience informs the show’s exploration of how the brain heals itself and ultimately creates the mind,” Lyras says. And the process is dramatically augmented by the visual effects of video designer Corwin Evans, using multiple projectors to create 3D impressions. The innovative music composed by Ken Rich, the set and lighting design by Matt Richter, and the editing by Peter Chalkos all coalesce to form a nearly perfect theatrical event. And that’s not easy to do with a solo performance on a subject so esoteric that it boggles the mind. The Hudson Guild Theatre is located at 6539 Santa Monica Blvd. in Los Angeles.